Westleigh, a suburb in Sydney’s North, is probably best known for being home to the house from the 1976 film Don’s Party. The sleepy suburb is surrounded by bushland and one of Sydney’s better-known trail centres, H2O.

With about 9km of community-built trails, mountain bikers have been coming here since the 1980s, and it’s become one of the few places in Sydney where new mountain bikers can build confidence and skills. More recently, Hornsby Shire Council is in the midst of an effort to sanction a portion of these trails, nearly doubling the amount of legal singletrack in Sydney in the process.

Not even hitting double digits for trail distance, Westleigh has become the flash point of a raging debate involving a door-knocking campaign and an appearance from an Upper House MP from Lismore. It has escalated to the point the local shopping centre has even gotten involved and officially taken a side in the project.

There has also been a healthy heaping of misinformation and wild claims about how mountain bikers will force critically endangered species into extinction if this development continues.

How did we get here?

Back in 2016, the Hornsby Shire purchased the Westleigh Park land from Sydney Water with the goal of creating sporting facilities for the district. This means a couple of sports fields and bringing the mountain bike trails up to snuff.

Stretching back to the early 1900s, the site was used for agriculture, as a Night Soil depot — a euphemism for where human poo is turned into fertiliser — a borrow pit, treated wood storage, and RFS fire training (resulting in contamination with PFAS foam and asbestos) among other things. Right before the land was sold to the Council, Sydney Water was looking at changing the zoning changed to allow for a residential subdivision. It is currently zoned under R2: low residential density and E3: environmental management.

I explained that as the council keeps denying access for sensible places to build trails, all you’re doing is perpetuating the problem

The site is also home to patches of Sydney Turpentine Ironbark Forest which is listed as a Critically Endangered Ecological Community, and Duffys Forest, which is labelled an Endangered Ecological Community.

Around this time, Westleigh local Steve Wright took it upon himself to organise bush care and trail maintenance and put up some proper signage for the small network.

“I moved to the area around 2013, and back then, the trails were well known, but it was all hush-hush. People from the area would use the land to ride, and walk their dogs, and bushwalk, but it sort of felt like you were sneaking in through a hole in the fence,” he says.

The only formal club in the area was the Sydney North Off Road Club (SNORC); however after the Old Man’s Valley project was completed, the club had temporarily disbanded. So Wright and a number of the locals took it upon themselves to fill the gap, conducting informal bush care and trail maintenance.

“Around 2016, we made the Facebook group and began engaging with the community. I also created a logo and a map and everything in terms of getting it visualised by the community and making it more of an actual trail (network),” he says.

While Wright and the H2O crew were building steam, Dan Smith, who runs the MTB23 coaching business, had organised a meeting with the Hornsby Shire Council to inform them that SNORC was being resurrected and to restart the conversation about trails in the region.

“The premise of the first meeting we had was to sit down with the (Council) GM and the three gentlemen who managed these types of land tenures throughout the Shire. We sat down, and they were extraordinarily standoffish. They had a laminated A3 copy of the H2O map, and before I could even say anything, they were into saying, ‘You can’t do this here, you can’t do that there, you can’t do this.'” he says.

Smith explains the Council expressed its frustration with illegal trails around the Shire, to which he responded, “You don’t know the half of it.”

“I explained that as the council keeps denying access for sensible places to build trails, all you’re doing is perpetuating the problem,” he says.

Despite the rocky start, Smith tells Flow the outcome of that conversation was the Council acknowledging the existence of H2O, saying it wouldn’t be closed down and that more formal discussion needed to take place regarding the future of the site.

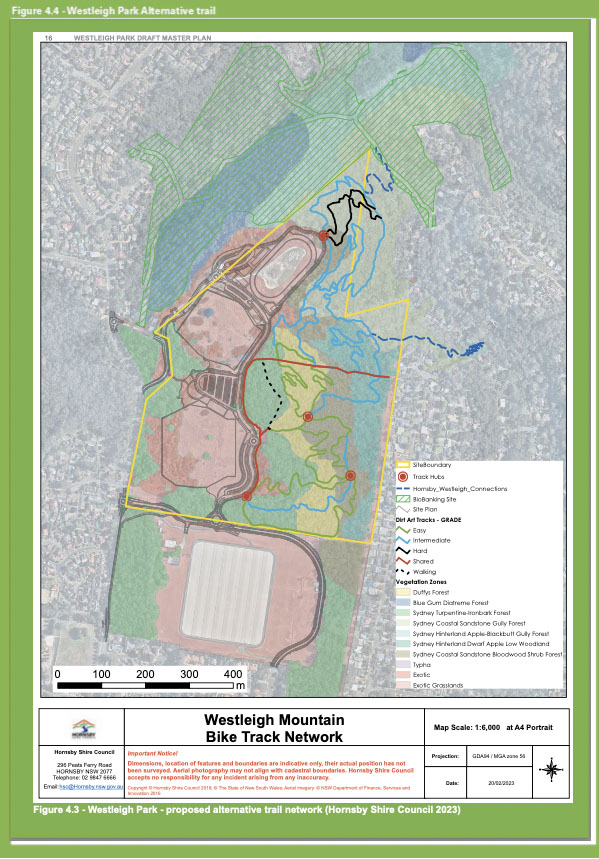

Thanks to a grant from the State Government, Council got to work on building a master plan. Trailscapes came in to audit the singletrack around Westleigh Park and proposed a couple of concept designs, including a broader vision for a connection between Westleigh and Old Man’s Valley.

This was circa 2018, and Council was ticking boxes it asked Wright and the folks from H20 to put a hold on any maintenance and trail care. This pause still stands — even after the insane La Nina storms that lashed the country in 2022 — which Wright tells Flow they have abided by. According to a Council, this request was made due to the asbestos contamination to prevent any soil disturbance.

It was an interesting discussion, because if you’re adamantly opposed to mountain bike trails being in there, that’s really no different than having a walking trail in there — the impact is the same

“The whole trail network and the approvals of the development are all tied in with the three sporting fields at Westleigh. The Council had a master plan for the actual ovals, and the trails are sort of on the fringe of that development zone,” explains Jason Lam from Dirt Art, which took over where Trailscapes left off.

“In the Draft Master Plan, the Council put sort of a nominal concept design forward, but they didn’t have a whole lot of consultation with the mountain bike groups and the other user groups prior to releasing those concepts. For the Council, it was sort of just squiggly lines on maps, but people took it literally, and it upset a bunch of people on both sides,” he continues.

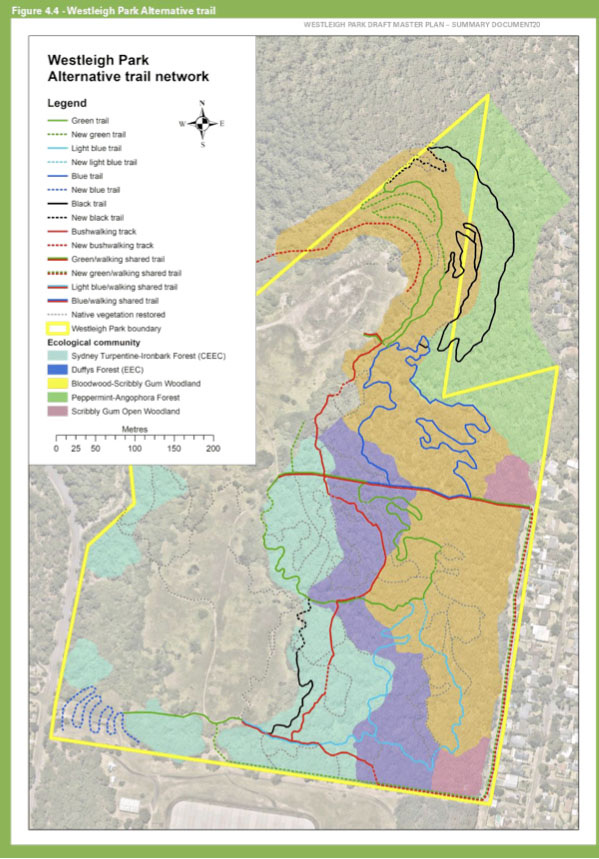

The Draft Master Plan released in 2021 didn’t put any numeric distances out, but based on the lines put on the map, showed a significant reduction in the trail, and some of what remained traversed the CEEC forest. There was a groundswell of outcry on both sides and a petition which garnered over 3,000 signatures from mountain bikers asking the Council to try again.

Take two, in-depth community consultation

With the Council headed back to the drawing board, the decision was made to enter a co-design process. Stakeholders from both sides were invited to participate and share their vision for the future of Westleigh Park. Captivate Consulting managed the process and Dirt Art was engaged to put together the trail design.

According to a spokesperson from the Hornsby Council, “Extra public consultation around the mountain bike trails was sought to address strongly held and opposing views around mountain biking through critically endangered ecological communities at this site. The aim was to co-design a trail alignment that ensures the long-term protection of the ecologically sensitive areas while still providing a quality riding experience.”

The engagement activities started with one on one phone calls with stakeholders, counsellor presentations, and stakeholder workshops. There was also webinar featuring Professor Catherine Pickering from Griffith University, Phil Downey a local mountain biking representative, and Steve Federow Hornsby Shire Council’s Community and Environment Division Director and the co-design workshops.

“This is the most comprehensive consultation process I have ever been involved in,” says Lam.

Based on the reaction last time around, this consultation was run differently, and Lam tells Flow the Council didn’t ask him to design anything before the engagement sessions. Instead, the goal was to find some consensus during the first workshop, and then he would come back with a concept trail network to be further refined.

“Both groups were very passionate in terms of what they saw for the site, and the mountain bikers were conceding a lot in terms of losing a lot of trail. I personally feel like we really did find a happy middle ground, but some of the individuals in the environmental group just flat out didn’t want any trail in there, whether it was walking or riding. And in the end, the environmental groups were like, no, we still can’t endorse it, which I think is a bit of a shame,” he says.

According to Lam, the anti-mountain bike side was composed of two groups. One had never been to the site, and the other frequented the site, walking on the existing trails.

“It was an interesting discussion, because if you’re adamantly opposed to mountain bike trails being in there, that’s really no different than having a walking trail in there — the impact is the same,” he says.

During the presentations, Lam came prepared with examples of mountain bike trails Dirt Art has designed and constructed in extremely sensitive environments, like Kosciuszko National Park and the World Heritage Rainforest some of Maydena traverses.

“It kind of opened some of their eyes to the fact that trails can be built in highly sensitive environments. It just needs to be done properly. It was a difficult space because a lot of the people against the project haven’t been to these places, so they can only take what’s being presented to them at face value, not from their own experience,” he says.

They were showing up at people’s doors with a clipboard and their bush hats saying ‘can we talk to you about mountain biking at the park and the sports fields.’ People would say I’m not interested, and they would keep talking and carrying on and claiming that all the bush was going to be destroyed

The games begin

In March 2023, Sue Higginson, who at the time was a Member for the State Electoral District of Lismore — she was elevated to a post on the NSW Legislative Council in May 2023 — appeared in a video with Hornsby Council Member Tania Salitra, who was running for a federal seat.

Why did a member from Lismore decide to hop in the car and drive eight hours to weigh in on a project being run by the Hornsby Shire Council? Flow contacted MP Higginson to find out, but our request for comment has not been acknowledged at the time of writing.

In the video, MP Higginson claimed that the “intensive mountain bike trails” at Westleigh, most of which garner a green rating, are pushing the Sydney Turpentine Ironbark Forest to the brink of extinction. Of course, we should note these trails have been at Westleigh following these alignments since the 1980s.

She goes on to say that she’s in favour of mountain bike trails in appropriate places. Flow asked MP Higginson if she was aware of the current amount of legal singletrack available to Sydney residents and if she supported the concept design that resulted from the co-design workshops. Again we’re yet to receive a response to our questions. MP Higginson would go on to assert that mountain bikers hold immense political influence, before insinuating Matt Kean, a Member for Hornsby, who at the time was the NSW Minister for Energy and Environment, is the ring leader of an MTB deep state apparatus pulling strings to get less than 10km of singletrack built in the suburbs.

In the same eight-minute clip, Cr Salitra makes sweeping claims that, “there is a growing body of scientific evidence that mountain biking does damage the environment so much more so than just walking trails” and “the scientific consensus is that mountain bike trails through sensitive vegetation…just isn’t actually possible, and that’s whether its formalised or informal trails.”

Flow contacted Cr Salitra to ask if she could share the source that lays out this consensus and the disparity in impact between mountain biking and hiking trails. Unfortunately, our request for comment has not been acknowledged at the time of writing.

According to this 2007 study which is linked on the Environment NSW website and referenced in the supporting documents for the Illawarra Escarpment Mountain Bike Trail Network Review of Environmental Factors,

“The environmental degradation caused by mountain biking is generally equivalent or less than that caused by hiking, and both are substantially less impacting than horse or motorized (sic) activities. In the small number of studies that included direct comparisons of the environmental effects of different recreational activities, mountain biking was found to have an impact that is less than or comparable to hiking.”

Another study — which one of the co-design presenters was a co-author — cited in the NSW Cycling Strategy Guide for Implementation, compares the impact of hiking, mountain biking, and horse riding on vegetation and soils in Australia and the United States of America said,

“Trail erosion and widening, soil compaction and vegetation damage on a recreational bike trail and a racing trail were recorded over 1 year in the wet and the dry season. Impacts were confined to the trail centre with few impacts to trailside vegetation, which is consistent with a past USA study (Bjorkman, 1998). Although the racing trail was wider after an event there was no widening over the longer term. The authors concluded that even though bike riders prefer downhill runs, steep slopes, curves and water stations (features related to higher impacts), mountain biking is sustainable so long as that trails are appropriately designed, located, and managed.”

We should note this is a literature review paper, and the major conclusion was that all three pursuits have impacts, and more research was needed.

Related:

We’ve devoted a lot of space on this page to this particular video clip and could write another 2000 words continuing to debunk claims made by this pair. However, it provides some insight into the poorly sourced information that forms the foundation of the resistance to this project.

For example, according to the timeline on the Save Westleigh Park website, following the land acquisition, the group insinuates mountain bikers built the first 5km of trail by 2017. In truth, the trails at Westligh have existed since before this writer was born.

But it’s not just online that this is all taking place.

In April, a post on the Westleigh H2O mountain bikers page queried if folks had seen a door knocker come through to ask for signatures on documents supporting Save Westleigh Park.

These people rocked up and protested on site while the co-design workshop was taking place

“They were showing up at people’s doors with a clipboard and their bush hats saying ‘can we talk to you about mountain biking at the park and the sports fields.’ People would say I’m not interested, and they would keep talking and carrying on and claiming that all the bush was going to be destroyed,” says Wright.

Shortly after this, the Westleigh Village Shopping Centre came out in public support of the development and asked people who had been accosting folks in the centre while they were eating and buying groceries to knock it off.

When it came to the co-design process, stakeholders were chosen through an expressions of interest process. As a result, some of the more vocal environmental groups were not included in the co-design. So they aired the grievances to the Hornsby Advocate, as they have on several occasions before.

Smith, the current President of the resurrected SNORC, was also excluded from the co-design.

“These people rocked up and protested on site while the co-design workshop was taking place,” he says.

Smith tells us this same group has continued to protest the development standing on the side of the road with placards.

When asked why specific folks weren’t included in the co-design process, a Council Spokesperson told Flow, “Selection to the co-design workshops was made through an ‘Expression of Interest’ process for Hornsby Shire Residents. An equal number of representations from each stakeholder group was sought and participants were required to meet a range of selection criteria. Therefore, not everyone who nominated to take part in the co-design process could be selected.”

What actually came out of the co-design workshop?

Among all of the drama, the co-design led to a concept trail network which considers the site’s sensitivity.

“It’s important to realise that there is a species of forest in Westleigh Park which is threatened and critically endangered, and the mountain bike community make it clear that trails should be removed from the Sydney Turpentine Ironbark Forest as much as possible with a well designed, well built and sustainable facility,” says Wright.

Removing the trails from the CEEC did involve losing some important green trail, and as Wright notes, they asked if something of similar value could be built in a less sensitive area of the park.

“What the Council came back with is a 27% reduction in trail at Westleigh, but 40% of the remaining trail will be brand new and sustainably built. We’re moving in the right direction, and the response that we’ve had is one of positivity and support for the process because the result will be a more sustainable and higher quality facility,” says Wright.

The most significant improvement for the trail network is that it will be a trail node format. As it stands, Westleigh is basically one big loop. This updated design will allow folks to create smaller loops and ride sections in different ways.

“It’s going to be geared towards green and blue trails, with very little black, because that’s catered for in Old Man’s Valley. What makes the trails so enjoyable at Westleigh is that you get different levels of riders that push themselves in different ways,” says Wright.

Westleigh sort of hits a market that Sydney doesn’t really have, and the reason it’s so popular is because it caters for that beginner market

“They’ve listened and reached out to the mountain bike community to understand what we want, and they get that if they don’t build a desirable facility, it will be a complete waste of money,” he continues.

Lam tells us the map which appears in the current Master Plan is close to what will be presented and voted on by the Council, however there have been a few slight refinements to reduce incursions into the sensitive parts of the forest. Of course, this is only a draft, and a detailed design process, micro-sighting and everything else will take place before shovels hit dirt.

Why is Westleigh so important?

Despite having what is likely the largest population of mountain bikers in Australia, Sydney only has a little more than 10km of legal singletrack — sanctioning Westleigh would nearly double that. There are a lot of reasons for this, but one of the big ones has to do with the amount of national park land that exists in the suburban areas. Traditionally NSW Parks and Wildlife hasn’t been amenable to mountain bike trails on the land it manages — though that’s changing. That being said, there are hundreds of kilometres of unsanctioned trails, most of which are tight, techy and rough.

“Westleigh sort of hits a market that Sydney doesn’t really have, and the reason it’s so popular is because it caters for that beginner market. I take new riders there because it’s the best place to start them off. So it’s actually an essential little trail network, small as it may be, for broader Sydney.”

“You’ve got the highest proportion of mountain bikers in the country, and you get the least amount of formal trail in the country. It needs to happen somewhere, but often the response is it’s not our problem, it needs to happen somewhere else — which is how you get so much unsanctioned trail,” says Lam.

The reason that illegal trails come into existence is that the infrastructure is not meeting the needs of the community. As we’ve learned with Old Man’s Valley, Golden Jubilee and Bare Creek Bike Park, creating good-quality facilities is a double whammy.

“Having a place like H2O does two things. It takes that energy away from digging in a national park, and for the Council, it’s a platform to engage with bush care volunteer groups and give them a better education,” says Smith. “It’s not just mountain bikers that will benefit from this, it’s also the athletics clubs. There’s going to be a crit track and facilities for the soccer clubs and AFL clubs — it’s a sporting precinct.”

The Hornsby Council will publish the results of any recommended amendments on June 5 at 5 pm and will take a vote on the Westleigh Park Masterplan and Plan of Management on June 14.

Photos: Tim Bardsley-Smith | Australian Mountain Bike Magazine / @TBSPhotography, Steve Wright, Flow MTB