Standing 1,390m above sea level, Mount Canobolas is an extinct volcano near Orange, NSW, with a paved road to the summit and as much a 500m of usable vertical drop — sounds like a no brainer for a mountain bike trail network, right?

The potential for something special is precisely why Rodney Farrell has been in the council’s ear since the early 2010s, pushing for a mountain bike trail network to be constructed on its slopes. In fact, in 2019, he even convinced us to pack up the Flow Mobile and set sail for the Central Tablelands to check out the trails around Orange.

“I’d just been showing councillors, staff and directors at the city council some of the good news stories about mountain biking. You know, Rotorua seeing more income from mountain biking than logging; Whistler’s biggest days on the mountain coming during the summer rather than winter — things like that,” he tells Flow.

Farrell and his wife had put together a proposal and submitted it to the council. Then, after the Electrolux manufacturing plant in Orange shut down in 2016, he got a phone call asking if the project had legs.

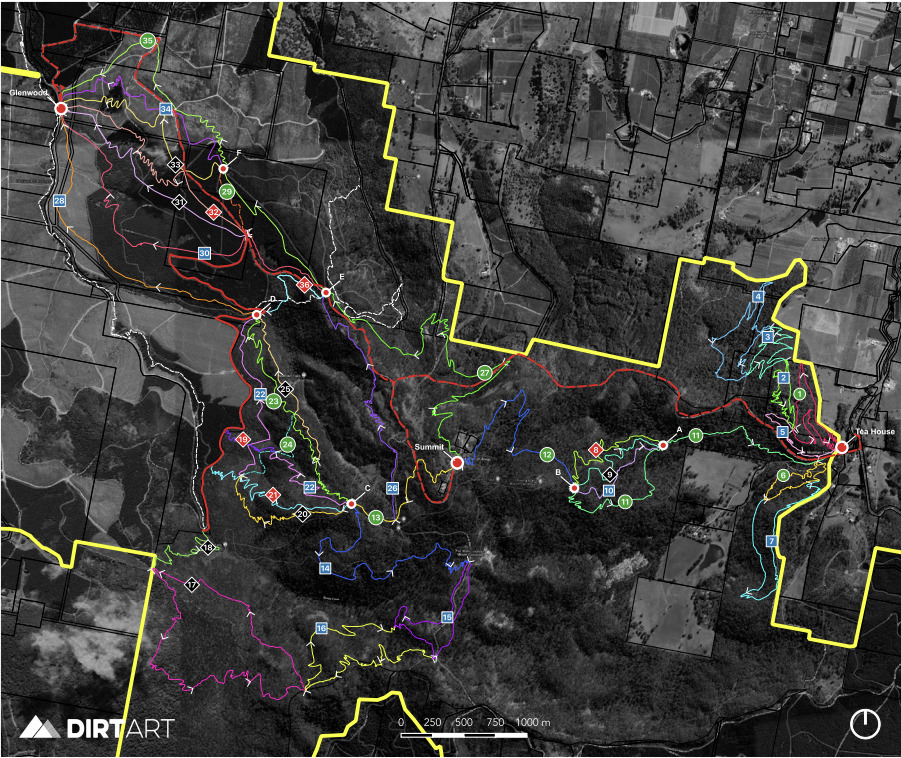

Since then, the Orange City Council has been working to make this project a reality, and Dirt Art has mocked up a concept design outlining a trail network with between 90km and 100km of singletrack. With the size and scale of this project, it has been flagged to undertake the State Significant Development approval process, and the first round of reports have been submitted.

Unsurprisingly the riding community is stoked about what’s in the pipeline. Three successive mayors have also backed the proposal, and candidates vocally supportive of the project swept the most recent local elections — not a bad litmus test of broader community support. However, a group vocally disapproves of this project, and that opposition has devolved into name-calling and mudslinging in the media.

Related:

- What did we learn from the Warburton Mountain Bike Destination EES?

- Mount Remarkable Epic | New IMBA Epic Trail and family-friendly singletrack for Melrose, SA

- Crabs and cuttys on the Cassowary Coast | 96km trail network proposed for Cardwell, QLD

What is planned for Mount Canobolas?

Given the elevation on offer and the existing roads winding up the mountain, Jason Lam from Dirt Art tells Flow they’ve designed a gravity oriented network.

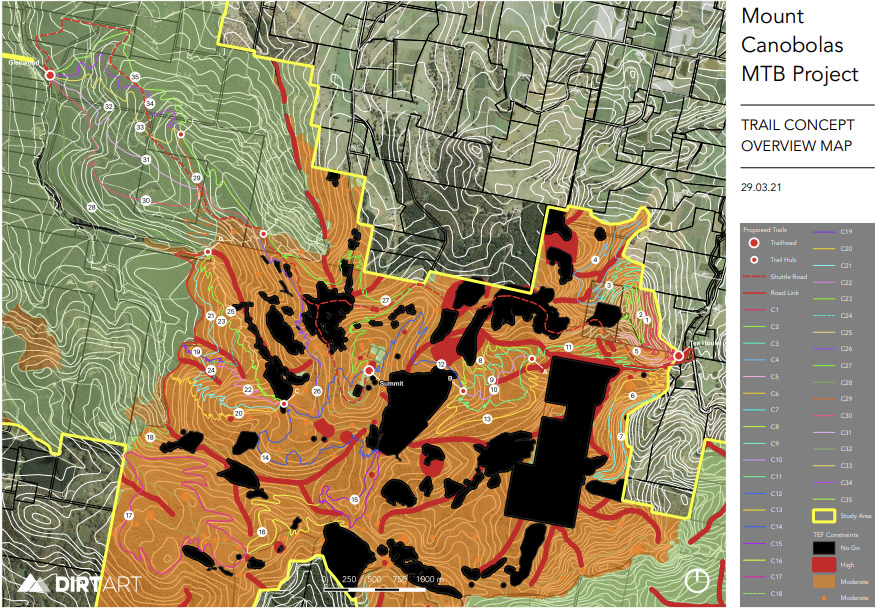

Based on the environmental constraints of the mountain, the network has been divided into four zones, which traverse unique environments and cater to different styles of riding.

The first trailhead will be located near The Mountain Tea House on the eastern side of Mount Canobolas, where several XC and beginner loops branch out from the trail hub. From above, a single trail off the summit branches out into four beginner and intermediate gravity descents, which funnel back into the trailhead.

Going west from the summit, Lam tells us this zone lends itself to the gnarley descending opportunities, offering some steep janky tech.

“There is some cool rocky terrain, and that’s probably where the best scenic views are; it’s probably the most pristine area of the mountain, it’s stunning,” he says. “It’s also super rocky, so you’ll get some technical enduro style trails through there — it reminds me what you’d see at Stromlo. I think that will be quite iconic.”

Lam tells us there will be longer format wilderness loops offering a more remote riding experience on the southwest aspects of the mountain — he says this will be ideal for e-MTBs.

Working our way further around the compass, the northwest side of the mountain is where you’ll find longer format descending and some bike park style features.

“This moves into the forestry estate, and the gradient of the hill mellows out as you move into the pine plantation. So that’s where we’ve nominated for all the freeride jump trails because it’s been recently logged, so heavily disturbed with no cultural or ecological sensitivities. Whereas all the stuff (up higher) in the SCA (State Conservation Area) is more natural features with a much smaller footprint,” says Lam.

On this side of the network, there is a pre-existing flow trail along the Boree Creek River which will be incorporated into the network. An existing unsealed road runs from the proposed trailhead to the summit.

State significant development

New South Wales has a woeful amount of legal singletrack compared to other states, especially for its population. On completion, the Mount Canobolas trail network will be one of the biggest in the state. And because of this, the project has been flagged as a State Significant Development.

“Various clauses in the actual legislation trigger the State Significant Development. One of those is a spend of $10-million or more. Another is that it’s in an environmentally sensitive area and also (for) tourism. This project ticks all three of these boxes,” says Emily Cotterill, Director & Principal Consultant at The Environmental Factor, the outfit that conducted the ecological studies of the proposed network.

The project also runs across several land tenures, including a state conservation area, commercial pine plantation, state forests, and two council areas.

It’s not an exact apples to apples comparison, but the State Significant Development process is similar to the Environmental Effects Statement track in Victoria. The SSD Database is split between two websites on the NSW Planning site, but as far as we can tell, Thredbo is the only other mountain bike trail project that has been flagged for an SSD.

Farrell tells Flow that with this project, they actually wanted to go down the SSD track.

“Part of the reason we chose to go this route is that the project will come under heightened scrutiny. Orange City Council, who are the proponents for this proposal, have acted independently, and they are cleaner than clean on this. Going through the SSD means there is full transparency,” says Farrell.

The project has only entered the first stage of the State Significant Development, and a preliminary environmental impact statement has been submitted to the State Government. Once these reports have been reviewed, the project team will receive the Secretary’s Environmental Assessment Requirements (SEARs). This is essentially the powers at be looking at the work that has already been done and saying, ‘we’re concerned about these areas, we’d like further study on this, this and this.’

We didn’t just limit these constraint maps to threatened species records and official NPWS datasets. We included any data that local community groups sent through, as that is what was important to them — we kept all of it.

Working back to front

In most cases, when a trail network is in the early stages, a contractor like Dirt Art conducts a feasibility study. Then they put together a concept design and map everything out before heading into the field to flag and ground-truth the alignment. Once that’s complete environmental and archaeology teams will conduct surveys and flag any areas of concern for realignment.

Mount Canobolas is different, and a combination of the politics surrounding development on the mountain and the State Conservation Area, Orange City Council took a different approach.

“We worked from the other end of the spectrum. The environmental and archaeology consultants did all of their (desktop) studies first to highlight all the no-go zones. Then they provided us with a map overlay identifying conservation values of the area,” Lam tells Flow.

Lam took this map and then designed the network-based around this overlay, aiming the trails for less environmentally sensitive areas and drastically reducing the footprint if alignments needed to cross areas with an elevated conservation value.

“We’d only cross there once or twice, and we’d pinch all the trails together, to cross at a single point to reduce the impact,” he says.

These constraint maps are extremely detailed, and Cotterill tells Flow her team’s approach was to cast the widest possible net to gather data.

“We invited anyone and everyone to come forward with any information they had on the mountain — places of interest, pet projects, their favourite plants and anything they have seen, including the Canobolas Conservation Alliance,” says Cotterill.

All of the information that was submitted was included in these preliminary constraint maps, with ecological assets encased in a minimum 25m buffer.

“We didn’t just limit these constraint maps to threatened species records and official NPWS datasets,” she says. “We included any data that local community groups sent through, as that is what was important to them — we kept all of it.”

“We took it, put a 25m buffer around it and excluded these areas from impact,” she continues. “The archaeology consultants did the same with artifacts recorded, which were buffered as well.”

As part of this constraints process, a project control group was formed, which included Farrell, Cotterill and Lam, National Parks, members of the local indigenous community and the local land services, the threatened species team, the Crown Land team and Forestry Corporation NSW, among others — who all submitted data that that was also included in these maps.

All of this was during the desktop study phase of the project, and when the project team when into the field, a prickly surprise was waiting for them.

Overhead blackberry

Mount Canobolas is home to several unique species that only appear on its slopes, from a special community of lichens that occur exclusively on rocks near the summit to Eucalyptus Canobolensis (AKA Silver-Leaf Candlebark) and a protected mint bush. However, there are also areas that are severely degraded, and the trails were specifically aligned to utilise these zones of lower conservation value.

“Out of all the sites that I’ve visited and flagged trail, this is hands down the hardest flagging we’ve ever come across. It was head high blackberry everywhere, with inch-long thorns; it would just tear you apart,” says Lam. “You couldn’t just force your way through it like you can with lantana, and you had to sort of bash it down with a stick and walk across it like a ladder bridge.”

Inadvertently, by aiming for these areas of lower conservation value, Lam had routed the trails through areas taken over by bushfire regrowth, and invasive weeds like blackberry had flourished.

“The local environmental groups insist this place is absolutely pristine — which it’s not. I would say that close to 60-70-per cent of what we went through in the State Conservation Area was heavily infested with blackberry,” Lam says.

Once the alignments were flagged, the environmental and archeological teams walked the trails to conduct their surveys. If something was found, Lam rerouted the trail alignments on the spot to ensure whatever it was would not be disturbed.

“The archaeologists found a couple of artifacts whilst walking the proposed alignments, and the trail was rerouted then and there to avoid them. They had an Aboriginal elder or project Registered Aboriginal Party with them for that process to make sure there was an adequate distance from the trail,” says Cotterill. “Our ecology teams also flagged a series of previously unknown wombat burrows and noted where a number of plant community types started and stopped.”

Cotterill pointed out to Flow that through this ground truthing process, the ecology and archaeology teams contributed to the mapping and data resources on the mountain and provided information on biodiversity assets and vegetation condition that was previously unknown. This was owing to the teams traversing off-track areas that are difficult to access due to both terrain and, in some places, heavy weed encroachment.

Once the ground-truthing process was complete, the reports were written, the concept design was updated, and everything was provided to the project control group. Each stakeholder was allotted veto power if any individual felt something was not above board. According to Lam, Cotterill and Farrell, there were no objections, and the collaborative tick of approval was provided.

The opposition gets loud.

With any project, regardless of whether it’s a mountain bike trail network or new lines painted on the street, there will be a group of people who are opposed to it for one reason or another. And some opposition is good because it provides a gut check and can lead to a better final product.

The Mount Canobolas mountain bike project is not unique in that there is a group opposing it, and they have made their case to anyone who will listen. But, unfortunately, opposition becomes an issue when lines of communication break down, and the conversation transitions from fact-based objections to loud accusations based on emotion.

The conversation surrounding the Mount Canobolas project has descended into the latter. As a result, there has been quite a bit of mudslinging with increasingly lairy and easily disprovable accusations, which have made their way into local and national level news.

These range from telling the Central Western Daily that The Environmental Factor’s report relied solely on crowdsourced information rather than their own ground-truthing. The group also claims on its website that 30ha of native vegetation would be lost, despite the publicly available reports clearly stating that the impact footprint would be 17.2ha — a figure calculated on a worst-case scenario 2m wide footprint, and the trail corridor will likely be narrower. They also claim weeds are not a problem in the SCA.

Another news story published by SBS claims the Orange City Council commissioned an archeological report that only found one heritage site. The text of the constraints summary report outlines over 30 heritage sites, which are also mentioned in the report from Dirt Art.

Finally, the group is also unhappy that the project has been submitted as a State Significant Development, stating it shifts the decision making power to the Department of Planning Industry and Environment, rather than the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service — who already gave their tick of approval as part of the stakeholder group.

Attacks have also been levied at the credentials and credibility of the folks who have contributed to the body of work surrounding this project.

“We are environmental scientists and hold as our professional duty, protection of the natural environment, including biota contained within our National Parks. We are not for or against Mountain Bikes. Our job is to undertake a scientifically objective assessment and pass this information on to those who will make the final decision as to whether the project will be approved. That’s exactly what we have done,” says Cotterill.

“Council have never pushed us for the answer they want. They’ve always said if you find a no go, it’s a no go,” Farrell continues.

Taking a positive from a negative

Everyone we spoke with about this story was disappointed that a project that should be full of fanfare and excitement has devolved into mudslinging and accusations balanced on wobbly foundations, and Farrell told Flow this is not an ‘us vs them’ thing, nor has it ever been.

It’s clear that people care deeply about what happens on Mount Canobolas, but it seems there may be a lack of understanding of what’s actually being proposed — heck it even happened with Derby.

“There is a big misnomer with people who don’t understand and think they’re going in there with big dozers that are going to plough straight through the place. Whereas the people who understand say, ‘well actually they have surveyed the area over four seasons, on foot with a wide corridor with a view of putting in something that’s 90cm wide,” says Farrell.

All of this empirical work is expensive, and the council has spent $500,000 dollars to get to this point — a common talking point of folks who are against the Mount Canobolas mountain bike project. But that half a million dollars is in pursuit of a $30-million return according to the council’s modelling.

“New South Wales is just starved for mountain biking, and Orange is accessible from Sydney, Newcastle, Wollongong, and Canberra, and this will be a year-round riding destination with different flavours in different zones to ride in,” says Farrell. “The council has never tried to water down the network. They’ve trusted our vision and are willing to let the pros do their job, so that we can make something world-class.”

As it stands in New South Wales, there isn’t a trail riding destination currently offering this volume of singletrack — there are some in the works like Mogo, and of course, the lift access riding at Thredbo cannot be overlooked. We don’t have a crystal ball, and can’t predict what will happen on Mount Canobolas, but based on what we’ve seen, and the time we’ve spent eating and drinking our way through Orange’s food and wine scene, we’d wager it’s going to be epic if it does go ahead.