Josh Carlson awoke to his phone ringing in an unfamiliar, dark hotel room. At the other end of the line was a nurse inquiring what countries he had visited.

“I had no idea where I was, or what countries I had been in, because I had slept in four hotel rooms, in four different countries, for the last four nights,” says Carlson.

This wasn’t the result of a Bali bender or Covid fever-induced delirium. Instead, the Wollongong local was spectacularly jet-lagged from trying to get home from a truncated international racing campaign. After months of preparation to race the World e-Bike Series and EWS-E events, Carlson found himself coupled up in hotel quarantine in Sydney after only two weeks abroad.

Related

- Shimano EP8 Review | Long-term living with Shimano’s latest e-MTB motor

- Haz of all trades — the journey from BMX racing to Freeride MTB

- Surf and Turf with Jack Moir

- REVIEW | 2021 Giant Trance X E+ Pro 29 1 Talks the Torque

“I said give me a second, I ran to the window and opened the blinds, and I saw where I was. I picked the phone back up and was like, ‘look, I’m sorry. I’m in Australia, I’m in hotel quarantine, and I told her the whole process of how I got here — she was pissing herself laughing the whole time,” he says.

Carlson had planned to spend five months abroad racing in his first international e-XC and EWS-E races. Those plans changed when he discovered a well-hidden US entry requirement.

“Australian’s are allowed to enter the US directly, or from New Zealand, no worries. But, if you go to Europe, you’re not allowed back into the US without being outside of Europe for two weeks. You pretty much have to be back in Australia or New Zealand for 14-days before you can go back into the US,” Carlson says.

“I mentioned this to (Yeti Team Mechanic) Sean Hughes, and he was like ‘oh F***.’ Their entire Yeti program is based on doing the (European) EWS races, and then going to America and racing for a month in all the Big Mountain Enduro races that Yeti sponsors, and then back to Europe. In the last couple of days, I’ve ruined their entire travel plan,” he says.

Carlson was supposed to be on a similar program, flying to Europe and the end of May to race the EWS-E events on the continent before jumping back across the pond for a handful of e-enduros and e-XC races.

Carlson has set himself a daily pushup challenge during his two weeks in isolation.

Carlson has set himself a daily pushup challenge during his two weeks in isolation.

“Last minute that all got canned. I had accommodation all lined up, flights back to the US and race entries. Everything just got shut down because we couldn’t get into the US,” Carlson says.

Now stuck in isolation for two weeks, we caught up with the Giant Factory Off-Road rider to find out more about his travels and what he learned about e-bike racing on the international stage.

It can’t be e-XC. It needs to be e-MTB

Since the start, the e-Bike National Champion’s 2021 racing campaign has been unpredictable. Initially, the plan was to head to Innsbruck for team camp in April, allowing him to race the first World e-Bike Series (WES) e-XC in Monaco. However, when the Fort William World Cup was cancelled, the Giant team camp was delayed, and his first race would be the doubleheader WES event in Bologna, Italy.

The WES started in 2019, with the series receiving the UCI stamp of approval in 2020. But, unfortunately, it was only able to run a single event in Monaco before Covid19 shut everything down.

Back for 2021 with a six-round calendar, Carlson and his Giant team planned to use these events to get a better feel for the format, dial in some equipment, and prepare for the UCI World Championships and EWS-E rounds later in the year. At these two race days, Carlson got a bit more than he bargained.

“The big question going in was, how much does power to weight affect this race? I was adamant, ‘nah, it’s bullshit. I’m strong enough, I’m powerful enough, I can make it happen. It doesn’t matter how light they are; I’m confident I can stick with them on the climbs.

Well, it turns out that was bullshit,” laughs Carlson.

“The course in Italy was so biassed towards power to weight; it made it unrealistic for anyone else to race,” he says.

On both Saturday and Sunday, Carlson was off the back before the field had even left the starting loop because prolonged smooth, sometimes paved climbs made it a contest of who can post the smallest number on the scale, not who was the strongest or most skilled rider.

“The course was so steep and had so much sustained climbing, the entire field rode away from me like I was standing still on the start loop. And then all the girls rode away from me like I was standing still.

I crossed the start line on Saturday in dead last, and Sunday was even worse.”

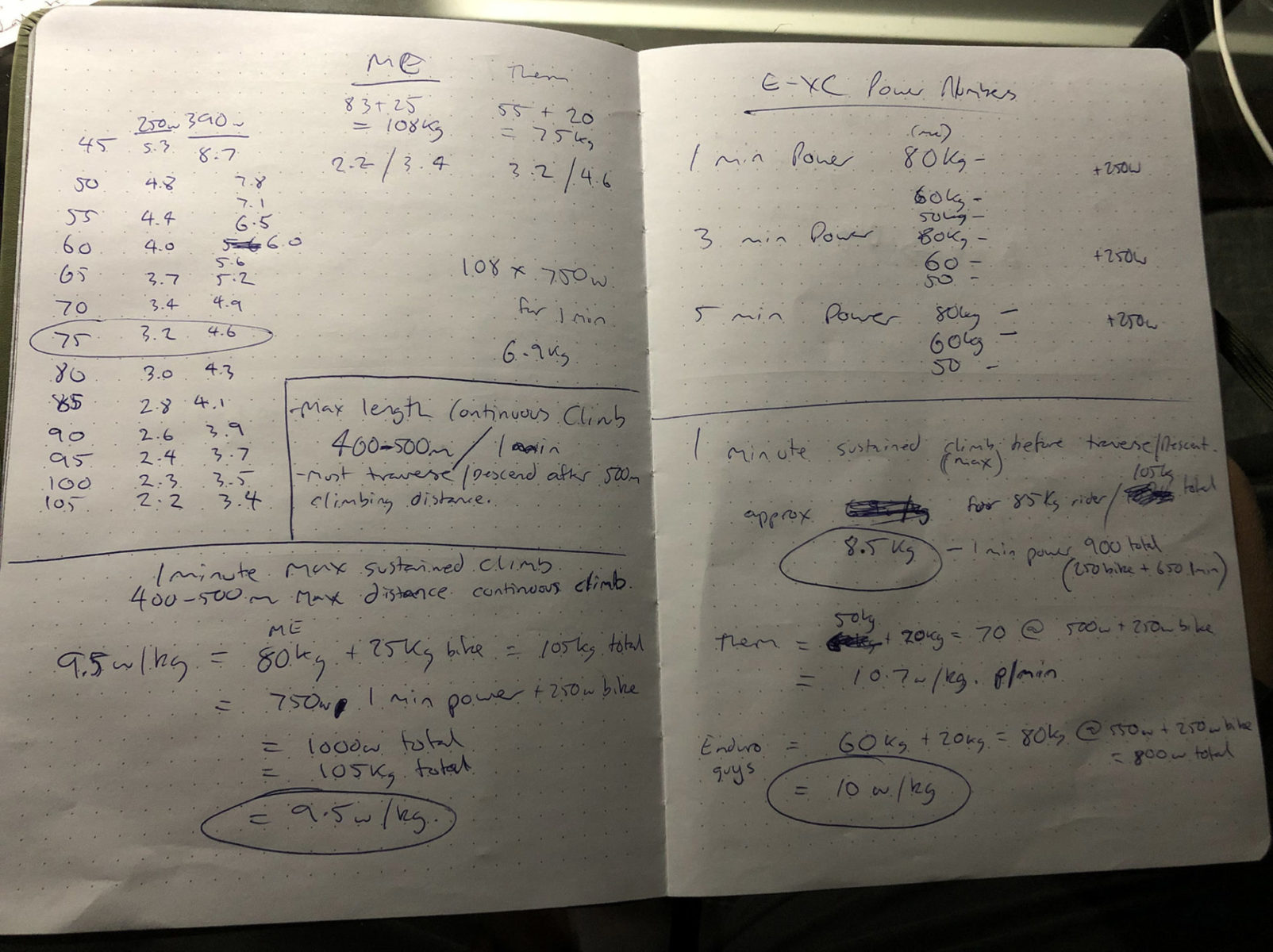

Carlson says these featherweight riders only need to produce about 250-watts on these sustained climbs to take full advantage of their e-bike package and hit the max speed limit. For the Aussie, who stands just over six feet tall and weighs 83kg, it would have taken something in the range of 600-700 watts to match their pace. To make matters worse, the descent played no role in the outcome of the race.

“The descent was so short and so simple, I could ride that like an absolute psychopath, and it didn’t make one word of difference. Say I was to ride that descent 20-seconds faster than anyone else, it didn’t even matter because I was losing 45-second on the climb to get to the top.”

“Don’t get me wrong. The power to weight ratio was for sure favoured to the lighter riders in Italy but the riders who were at the pointy end and inside the top 10 were the same calibre of rider that would be at an XCO World Cup. They are crazy strong, fit and committed to racing this discipline and are specific e-XC world-class athletes. Even as the sport evolves, I would expect the same athletes to be around the top of the timesheet even on a more suitable course”

Regardless of the racing style, different courses suit different riders, and genetics plays a role, but it should not be the only factor in the race. Even on the most pedally XC world cup course, bigger riders don’t get shot off the back of the field like they are riding in reverse before they leave the start loop.

“Look, I’m biassed because I am a bigger guy,” he says. “But if a guy my size and my height can be competitive, it shows the sport is in a good spot and is headed in the right direction. It shows the course, and the design, is all fair and equal, and you don’t have to be a 60kg whippet to race these things.”

Carlson says part of the problem comes from the UCI, and WES has been forced into appropriating the XC format.

“My personal opinion is that they’ve (the WES) been cornered into the XCO model, which is at a detriment to the development of the sport. It’s not e-XC; it’s e-MTB. The bikes are different, so it needs to be a whole separate model and course,” he says

“I think the UCI is part of the problem because they don’t have any idea what to do with eBikes, and they rely entirely on these other people and don’t provide any rules or guidance, or anything to help them,” he says.

“If that kind of course shows up again, it will kill the format.”

Carlson is not the type of person who is capable of sitting still, and he runs at about a million miles an hour, 24-hours a day. So with the prospect of being stuck in a hotel room for two weeks, he put on his thinking cap and might have come up with a solution to the problem with e-XC racing.

“The most sustainable number that’s comparable between a 50-kilo rider and an 80-kilo rider is about a one minute power. So for one-minute power, we can be within one watt per kilo; if I’m holding 750 watts for a minute, they are holding 500-watts for a minute, that’s about 8.5w/kg to 10w/kg.

On paper, this all works out, and it makes sense, but what about in the real world?

For those who don’t have much experience analysing power data, watts-per-kilo refers to how many watts an athlete can produce for every kilo of body weight. Power to weight on flat ground doesn’t make much difference; a 60kg rider and a 75kg rider pushing 200-watts will go about the same speed. But up a hill, if these same two riders are doing 200-watts, the heavier rider will be slower because he has to drag that extra weight up the hill, and his watts-per-kilo is lower. To maintain the same pace, a heavier rider will need to produce more power.

When we look at the Strava data shared by Mathieu Van der Poel and Ondřej Cink from the Nove Mesto World Cup, the Czech rider weighs 68kg and has a one-minute power of 568-watts, while MVDP tips the scale at 75kg and had a one-minute power of 645-watts. This works out to 8.4 w/kg and 8.6w/kg, respectively. The numbers don’t line up perfectly; however, it shows proof of concept.

Current e-XC world Champion, Tom Pidcock, who weighs 50kg, did not make his power curve public from the Nove Mesto World Cup.

This one-minute power between 8 and 10-watts-per-kilo is what Josh Carlson believes is the solution to making e-XC races about rider ability and not who is the lightest on the scale. He tells Flow if all the climbs were limited to about a minute before there was a traverse or descent, it would level out the playing field.

Fortunately, Carlson says the people behind WES are well aware of this and are open to feedback and evolving the format.

“The EWS is all singing all dancing now, but back in 2013, 2014 and 2015, we had heaps of teething problems. It took years for everyone to be happy and for the EWS to find the right format. Even from 2016 to 2017, it changed, and from 217 to 2018, it changed again,” he says. “This (WES) format is only brand new, so there are bound to be some growing pains.”

The main event — EWS-E

While e-XC racing is still finding its niche as a format, where the racing balances the capabilities of bikes and riders with how much they weigh, there is still a larger question of does it make sense. Is this format going to work, or will it become this tiny little niche, the likes of bike ballet or bike polo? Enduro, on the other hand, doesn’t have this same problem.

“These (e-Enduro) bikes are the bikes that people are buying, and they are the bikes we (Giant) are making. We’re not making a 120mm, 20kilo cross country bike; we’re making a 170/160mm all-singing, all-dancing, downhill smash machine, that can climb up mega steep hills and smash down anything you want,” Carlson says.

Enduro has created a tidal wave in mountain biking, arguably affecting every other racing and riding format — from the way we approach bike design, to the way new trail networks are laid out. The big problem is that enduro racing doesn’t broadcast well, and it’s a nightmare for production teams and media outlets to cover the races.

“There is potential for e-Bikes to become the premier Enduro category. In four or five years, once it finds its feet, the way that you can bring the event closer down to the people, and it doesn’t have to be so spread out with chairlifts, gondolas and shuttles and then hike 40-minutes to the top of some epic peak.

Ebikes allow you to condense all that,” he says. “You can do all these up and up, up and down, up and down stages, which is really cool for the spectator, cool for the development of the bike, it has potential to be something completely different.

The future of e-Bike racing

E-bike, racing as a format, is still in its infancy, and Carlson sees this as where things are headed in the future. But this isn’t the first time that Carlson has found himself racing a discipline that is still evolving, which fans, racers and even the event organisers don’t fully understand yet.

“I feel like I was at the start of the Enduro movement back in 2011-2012 when I moved to America and was at the first EWS. I’ve already had this conversation back then with everybody trying to explain what’s enduro? What’s an EWS? What are you doing? Where are you? Why aren’t you racing cross country?

So now I’m racing e-Bikes, and it’s the exact same conversation; what are e-Bikes? What is e-bike enduro? Where are you racing? Why aren’t you racing enduro?” he laughs.

“E-bike racing is where the money is, that’s where the future is going. If I had let my ego grab hold when this (eBike racing) scenario was presented to me, I would probably be calling it quits on my career. I would be in trouble or under an immense amount of pressure — this year would be make or break,” he says.

Even for riders at the pointy end of podium contention, it is tough to earn a pro contract — just look at what happened to Jack Moir when he left Intense Racing. This is an even taller order for riders who find themselves a bit further down the results sheet.

“If you’re a battling enduro rider or a cross country rider right on the cusp, and you were to hit up Peugeot or Gasgas, or one of those European companies we have never heard of, and present a package to go and race WES. That looks really impressive on paper,” Carlson says. “Or you can go get fiftieth in the World Cup — nobody knows the guy’s name who got twenty third in a World Cup, much less fiftieth. If you were in this (bike racing) as a business, you would be crazy not to.”

“And even talented women, someone like Sian Ahern, if she had the opportunity to come across and race an EWS-E, she’d probably win the thing. She has the potential to be on the podium at the EWS if she has the chance, but the opportunity for a girl to race EWS on a factory team is tough to get, whereas, at the moment, there is this open chequebook of eBike potential.”

What’s next?

Unfortunately for Carlson, he left the hotel quarantine and entered lockdown — talk about bad timing. Even though he only raced twice in this quagmire, the knowledge gained from those events has informed his training for the rest of the year and given some of his expectations a reality check.

“In the back of my head, I had a pretty big goal to perform well at World Champs at the end of August in Val Di Sole, but that was all hinging on how this e-XC race went. Don’t get me wrong, I’m going to go and pedal as hard as I can and give it a red hot go, but unless the course dramatically changes — it is what it is,” he says.

His primary focus is now on EWS-E events in Crans Montana, Switzerland, Finale, Italy and Tweed Valley, Scotland. However, Carlson also says there are a few eBike races in America which he is eyeing off, and now that he has been outside of Europe for more than 14-days, he should be able to enter the US.

Looking to 2022, Carlson says his plans are still very much in the air, but he will be racing the first two EWS stops in Derby and Maydena — on a naturally aspirated bike.